Judah Touro Cemetery

For someone who was described by one who knew him as “not a man of brilliant mind; on the contrary, he was slow, and not given to bursts of enthusiasm,” Judah Touro had quite an eventful life. In 1797 at the age of twenty-two, he went on a voyage from his home in Boston to the Mediterranean Sea with a ship full of his uncle’s cargo when the ship was attacked by pirates. Two years later, he was asked to leave his uncle’s home, possibly for asking his cousin’s hand in marriage. As he set out to find his way in the world, he was robbed in Havana, Cuba, and had to find work just to pay for passage to New Orleans.

Starting from scratch, he built a business empire without ever taking out a loan. Already an established businessman and near the age of forty, he volunteered with General Andrew Jackson’s army to defend New Orleans from the British. He spent the battle carrying cannonballs and gunpowder for the cannon batteries while under tremendous fire where other men dared not go. He was horribly wounded by a twelve-pound shot and left for dead. One of his only close friends, Rezin David Shepherd, brought him home and spent a year nursing him back to health. At the end of his life, he was estimated to be one of the ten richest men in America. One of the most extraordinary things about him was the will he left, in which almost his entire estate of close to half a million dollars was given to charity. Historians disagree whether he did it of his own good will or was heavily persuaded.

Every city in America with a Jewish community was remembered in his will. Cincinnati was given five-thousand dollars each for the Talmud Yelodim School and Jews’ (later known as Jewish) Hospital, and three-thousand for Congregation Bene Israel (aka Rockdale Temple). Along with Cincinnati, other cities included in the will included Louisville, Memphis, Montgomery, Savannah, Charleston, Mobile, Richmond, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Albany, New York City, and more. Due to his generosity, memorials to Judah Touro’s name were to be found everywhere and on all sorts of things: a hospital in New Orleans, a steamboat (which was sunk by the Union during the Civil War), a ship, a synagogue in Newport (named for his whole family), a university, plaques, a frieze of his face in the State House Capitol of Louisiana, and, in Cincinnati, a cemetery.

Thanks to Touro’s charity, Jewish Hospital was able to buy its own building and no longer needed to rent space. The Talmud Yelodim School, as well, would buy a lot and begin building their own schoolhouse with the money. All three institutions would put up eloquent plaques in honor of Judah Touro and his donation. Still, if no money was earmarked for a cemetery, why was it named after him?

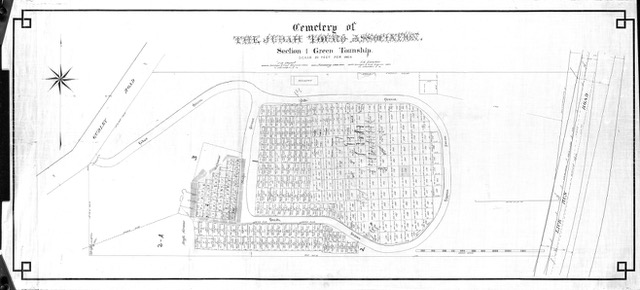

On December 2nd, 1855, a month and a half shy of a year since Touro’s passing, the Judah Touro Verein (pronounced ver-ahyn, German for Society or Association) was established. The purpose of this association was to create a cemetery completely independent of any local synagogues to allow burial of anyone who was a Jew, regardless of affiliation. For various reasons, this group of people did not want to use the cemeteries under the ownership of any congregations in town. The Society bought the land where Judah Touro Cemetery stands today, the area then called Lick Run. When they bought it, the cemetery was four miles outside the city.

Interestingly, the Judah Touro Society raised the ire of at least one Cincinnatian, Rev. Dr. Max Lilienthal. In a caustic public letter written to the Israelite, he referred to the society’s “laws and statutes of which aim at nothing less, than the ruin and destruction of all synagogues, the divine service and its appurtenances.” His letter ended with the following sentence, “We hope that the congregations, for the interest of self-preservation, will exclude all the members of these societies from any enjoyment of the privileges or the participation of the divine service of the congregations.” It seems from the letter that he felt that the society was a scheme to get out of paying membership dues to the synagogues in town. An advertisement to the Israelite a week later asked that all members of the Judah Touro Verein attend an extra meeting to discuss establishing a school for their children. This seemed to add more fuel to the fire. In a letter to the editor, the Judah Touro Verein wrote that the reason for the meeting was because members of the society did not wish to send their children to a school where “the superintendent…attempts to injure the J.T.V.,” and ended with the statement, “We cannot prevent the doctor from prejudicing his friends against the J.T.V. but we must assure him, the Verein will take no notice thereof.” It seems they didn’t, and we therefore have the Judah Touro cemetery. Why exactly this Verein picked the name Judah Touro, though, we might never know.

Sources

Klinger, Jerry. “Judah Touro.” http://www.jewish-american-society-for-historic-preservation.org/images/Judah_Touro_-PDF.pdf

Korn, Bertram W. “A Reappraisal of Judah Touro.” The Jewish Quarterly Review, vol. 45, no. 4, 1955, pp. 568–581.

The Judah Touro – Verein: OR THE RADICAL REFORM SOCIETY. Israelite. 2 May 1856, p. 349.

Classified Ad. Israelite. 9 May 1856, p. 355.

“The Judah Touro Verein.” Letter to the Editor. Israelite. 16 May 1856, p. 367.

“Judah Touro Verein.” Israelite. 10 Dec 1886.